- Find a Doctor

-

Services

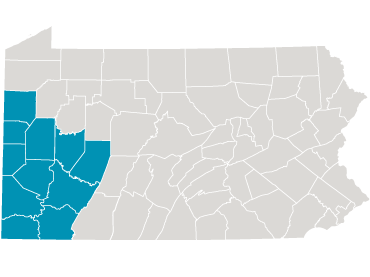

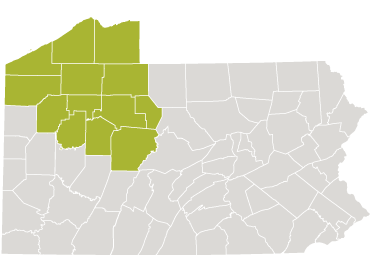

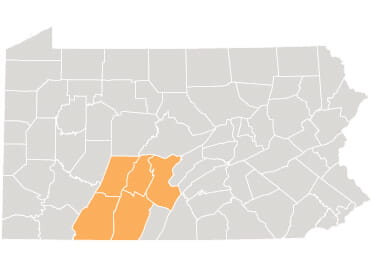

Frequently Searched ServicesAllergy & Immunology Behavioral & Mental Health Cancer Ear, Nose & Throat Endocrinology Gastroenterology Heart & Vascular Imaging Neurosciences OrthopaedicsFind a UPMC health care facility close to you quickly by browsing by region.

-

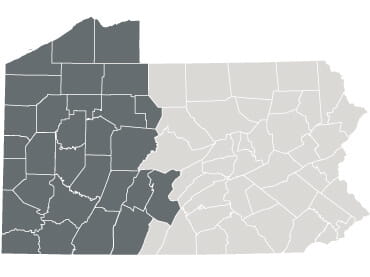

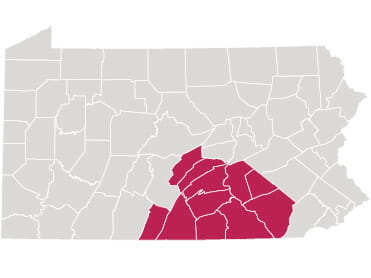

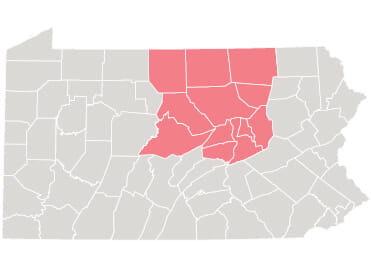

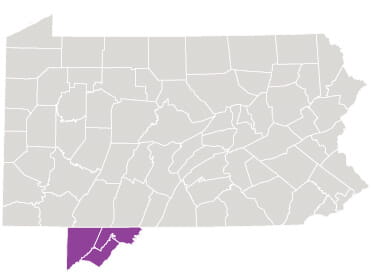

Locations

- Patients & Visitors

- Patient Portals